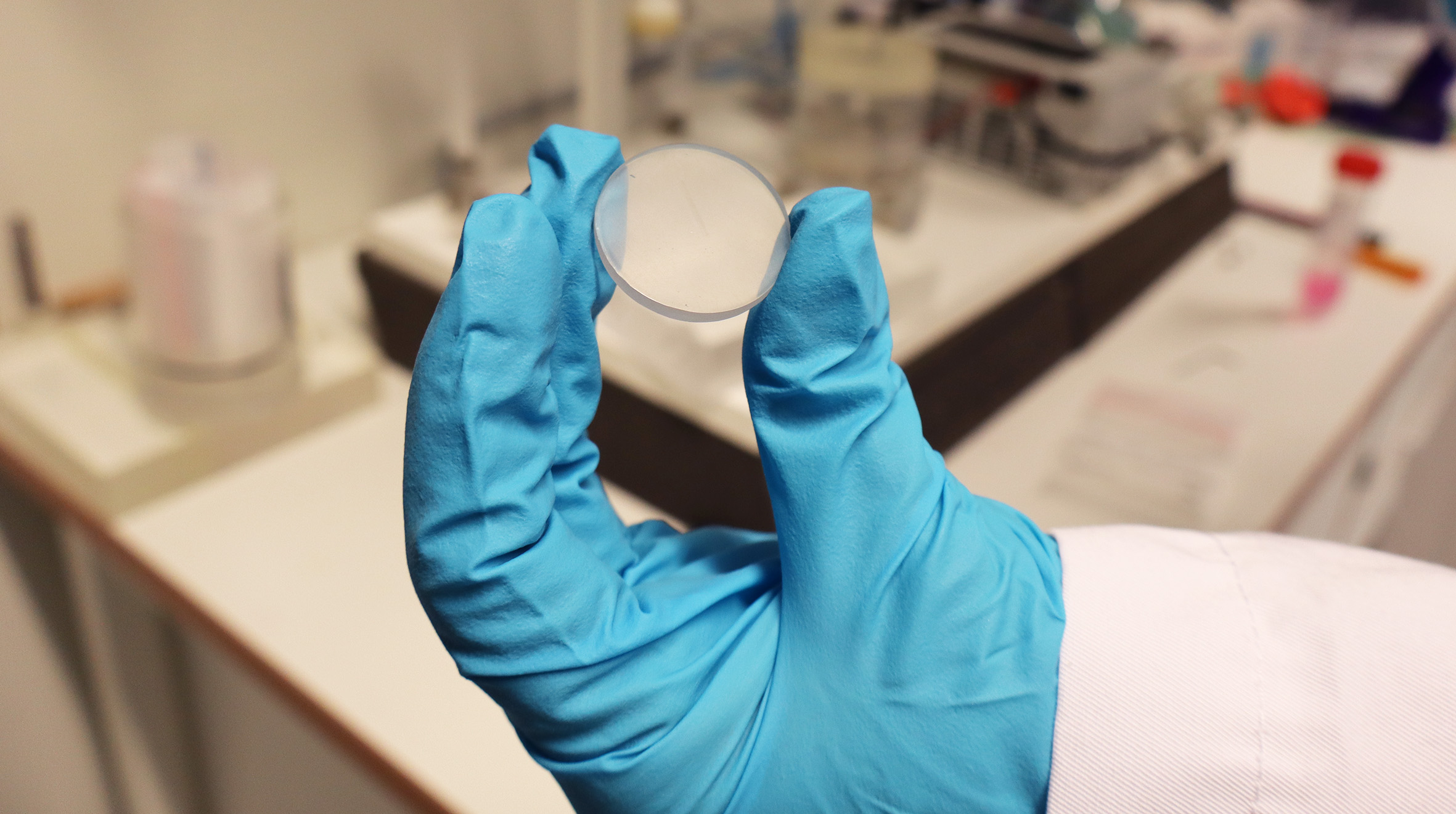

The materials in focus were used in occlusal devices such as bite splints, which are often worn at night to protect teeth. These devices are subjected to mechanical stress over time, which may lead to the release of microscopic plastic particles.

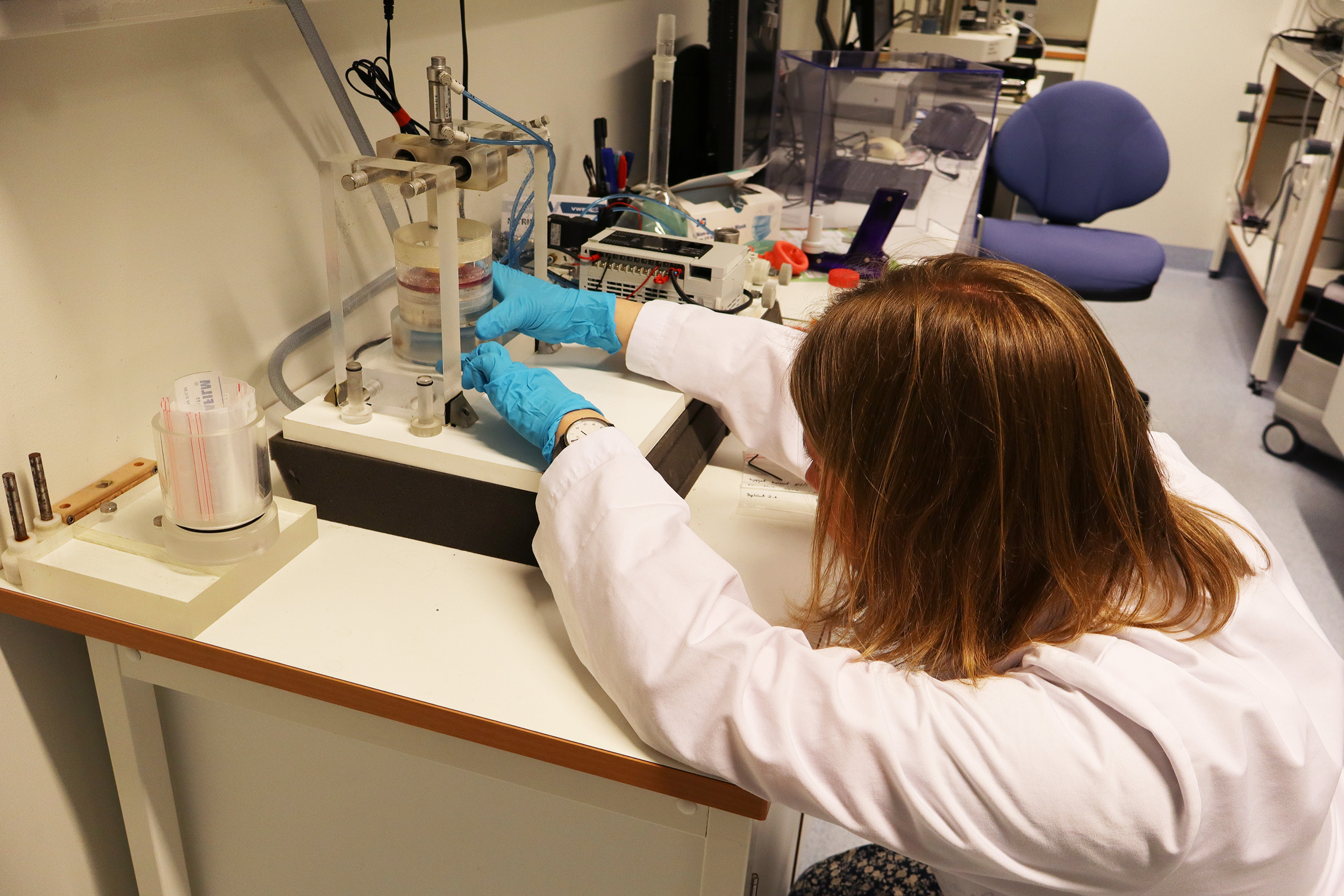

“We tested what happens when you apply mechanical wear to the materials – using a custom-built chewing machine – and then examined the microplastics that were released,” Kristine explains.

From plastic to cell reactions

Once the particles were isolated, Kristine and the NIOM team studied how they interacted with human epithelial cells. The results pointed to a biological response.

“When these cells were exposed to microplastics, we observed an immune response. The cells reacted – but what that means in practice is still not fully understood,” she says.

The research did not show that the cells died, but the exposure did seem to activate certain internal mechanisms.

“It didn’t kill the cells. But we could see changes in how the cells behaved. That suggests there’s something going on,” she adds.

The article continues after the photo.

Building on earlier work

Kristine’s work builds on a previous NIOM project that studied chemical leakage from similar materials. By adapting that experimental design, she added a new dimension to the study: solid particles.

“We based our approach on an earlier project and adjusted it to focus on microplastics. One part of the project was to look at the physical particles, how big they are, and whether their size varied depending on the material. In the second part of the study, cells were allowed to grow in an environment containing the micro particles to see what kind of response the particles caused.”

Nordic collaboration

NIOM’s facilities and staff played a crucial role in making the project feasible within a short timeframe.

“What has made this project possible is the team at NIOM. People here are open to trying things and have the technical skills to make it happen,” Kristine says.

The research was carried out in collaboration with senior scientist Jan Tore Samuelsen, dental technician and engineer Heidi Holm, engineer Susanne Croff Larsen, senior scientist Silvio Uhlig, senior engineer Torbjørn Knarvang and engineer Rugile Jakaviciute, who contributed with knowledge, laboratory work, and adjustments along the way.

NIOM is a Nordic competence center and visiting scientists like Kristine are part of a larger strategy to promote collaboration and mobility across borders. The institute gives researchers access to advanced laboratories, analytical instruments, and a team with broad expertise – conditions that are not always available elsewhere.

“Being here has helped me expand my research skills. I’ve learned new methods, worked with people with different backgrounds, and been part of a supportive research environment,” Kristine reflects.

The article continues after the photo.

Still early, but promising

The study does not provide a final answer to whether microplastics from dental materials are harmful. But it has shown that the particles may cause biological activity.

“As always in research, we started with a question and ended up with several new questions. That’s a good sign,” says Kristine.

There were no signs of cell death, but there were signs that cell function may have been altered. For example, the team saw potential effects on lysosomal activity – a process linked to how cells process material from their surroundings.

“There’s still work to be done to figure out the long-term effects,” Kristine says.

The future of the project

Kristine hopes the project will be continued by others at NIOM.

“There are many skilled people at the lab who know how we did the experiments and can build on it,” she says.

Her own next step has taken her to the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority.